Dryden resident facing drug trafficking charges

A 34-year-old Dryden resident is facing drug trafficking charges following an Ontario Provincial Police investigation. On Wednesday officers executed ...

11h ago

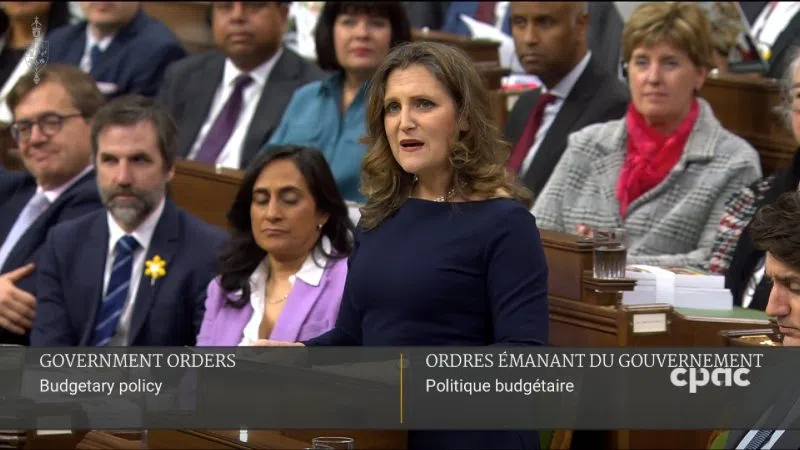

Tax hikes for Canada's wealthiest in federal budget

Canada's wealthiest earners will face higher taxes to help pay for increased federal spending over the coming years. An increase to the capital gains ...

11h ago

Housing numbers for the north questioned

The opposition is questioning the Ford government's housing numbers. The NDP says the government is padding the numbers by including new long-term car...

12h ago

Annual pace of housing starts fall 7% in March

Canada's annual pace of housing starts fell seven per cent in March. The seasonally adjusted annual rate of housing starts came in at 242,195 units. T...

19h ago

What's Happening on CKDR

"Check Out" Ontario Park Day Passes

Dryden Public Library, Ear Falls Public Library, Sioux Lookout Public Library, and Red Lake Public library are all listed as participants! Give your l...

13h ago

Red Apple Is Back In Sioux Lookout!

Lots of excitement in Sioux Lookout this past weekend! In fact it began on Friday when Red Apple's Grand Reopening in Sioux Lookout at 81 Front Stree...

Apr 15, 2024

Get Ready To Laugh!

Need a few laughs? 'Campfire Comedy' can help! 'Campfire Comedy' presents 'The Mark Menei Comedy Tour' with shows coming to several communities aroun...

Apr 10, 2024

Solar Eclipse 2024 in Sunset Country - Listener Images And Video!!

Despite overcast conditions yesterday afternoon in Northwestern Ontario not all was not lost went it came to seeing the Solar Eclipse! Thanks to a few...

Apr 09, 2024